Silkworms, responsible for the vast majority of commercial silk production, are Bombyx mori, domesticated and selectively bred from the wild Bombyx mandarina. When a Bombyx mori lays eggs, they usually hatch within 10 to 14 days. However, depending on the farmer's needs, they are often placed in the refrigerator for months, up to a year. Once warmed, they generally hatch within the same timeframe. Newborns must be fed immediately because they have a voracious appetite and will die very quickly from dehydration and starvation.

Bombyx mori have a preference for white mulberry leaves (their name is actually Latin for "mulberry silkworms"), and mulberry silk is considered the finest and most lustrous. Newborns eat constantly and go through five instars, the term for the stage of development between molts. Over a period of about 35 days, Bombyx mori sheds its skin four times, ending up 10,000 times heavier and 30 times longer than at hatching. Once they reach their fifth instar, they enter their pupal stage and envelop themselves in cocoons of pure silk.

The silk itself is secreted by two salivary glands in the head of the larvae and consists of two proteins: fibroin, the structural center, and sericin, the "gum" that cements the filaments.

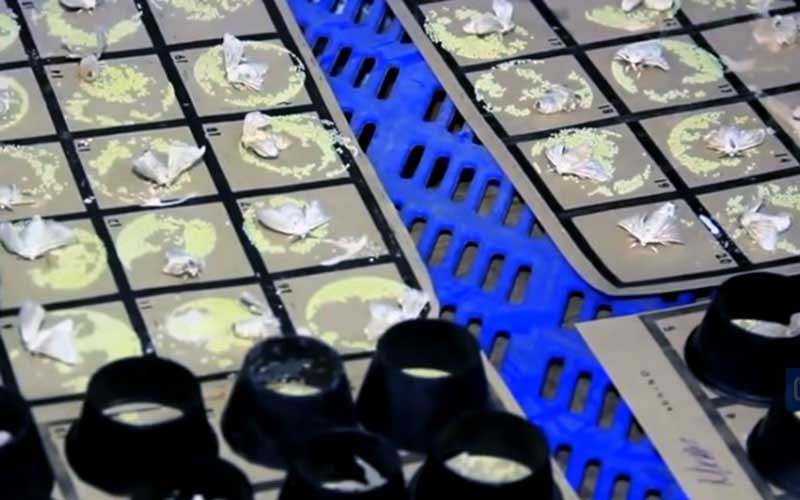

To emerge from their cocoons, the silkworms, at this stage moths, chew their way out, thereby significantly shortening the length of the silk threads and decreasing their value and the luster of the produced material. To prevent this destruction of raw materials, silk producers will stifle, which means kill, the pupae either by baking them, immersing them in boiling water, or, more rarely, freezing them or piercing them with a needle. This is usually done between two days and two weeks after the start of spinning, before they transform into moths.

Once the pupae are dead, the cocoons are then soaked in water to be more easily unraveled. The chrysalises are then discarded or, in some countries, eaten. If they were allowed to live after their pupal stage, they would emerge from their cocoons as moths, mate, lay eggs, and die naturally after about a week because they can no longer eat and depend solely on the nutrients they absorbed during their larval stage.

Another way silkworms are used is for the production of what is called silkworm gut, which is mainly used to make fly-fishing leaders. Silkworms are killed by methods such as submersion in a vinegar solution, just before they are about to spin and their silk glands are removed and stretched into solid threads, which look and feel much like plastic.

As to whether silkworms or insects in general are sentient and capable of feeling pain, studies conducted with morphine demonstrate that insect responses indicate a capacity to feel pain, but the scientific community remains in conflict. Silkworms possess a central nervous system and a brain and certainly display nociception (the reaction of sensory receptors caused by stimuli that threaten the integrity of the organism).

Even if we assume their death is painless—and we all know what assumptions are—it is still a death, and a human-induced premature death.

An alternative to this silk production method has emerged, called "peace silk" or "Ahimsa silk" after the Sanskrit term for non-violence. There are a number of sources and methods under the umbrella of "peace silk" and they are not all very different from the traditional approach. The most idealized version of peace silk is that which is harvested in the wild from empty silk moth cocoons.

Eri silk, for its part, is made from the cocoons of Samia ricini, which leave a small hole in their cocoon from which they emerge. This type of silk cannot be processed like Bombyx mori silk and represents a very small part of the silk market. Ahimsa silk is made from Bombyx mori that have been allowed to undergo their metamorphosis and emerge from their cocoons before the cocoons are harvested. Peace silks are more expensive and less shiny than traditionally cultivated silk, due to the torn cocoons, and represent only a small fraction of the silk industry in general.

The clarity of the actual practices of various peace silk suppliers can be difficult to determine. Silkworm breeder Michael Cook wrote an article criticizing various peace silk methods, highlighting the potential deaths inherent in the next generation of eggs and newborns and the unrealistic idealistic notion of wild-picked empty cocoons. Now, Mr. Cook himself raises and kills silkworms, so his contribution on the possible ethical conflicts of peace silk is interesting, to say the least. Peace silk producers have refuted and will refute such criticisms, but I think it is important to thoroughly and deeply study all so-called "humane" methods of producing animal products and by-products and ask whether the use of living beings in any form can be ethical.

Regardless of their treatment, the fact remains that domesticated silkworms are exploited for their silk. They have been selectively bred for the sole purpose of producing as much silk as possible, much like animals in the food industry that have been bred into disfigured absurdities too large to support their own body weight. The adult Bombyx mori cannot even fly. They also cannot eat due to their reduced mouthparts and small heads, a fact often cited as evidence of human manipulation, but this is true of all Saturniidae or giant silk moths.

The fact remains that these are living beings with paths of their own, with brains, nerves, and desires.